Monday, August 29, 2011

The melody of Pi

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Architecture in Pyongyang

This is the only time on record when the dictator is seen genuinely happy, dropping his guard and letting a smile. Ceaușescu visited the East Asian country in 1971, and was so impressed with the popular manifestations organized for him by Korean communist leader Kim Ir Sen that he decided to emulate what he had observed back in Romania. As soon as he returned from his trip, he tightened his grip on power, issuing what are called the Theses of July, a mini-Cultural revolution mandating a return to Socialist Realism in Romanian written and visual arts.

A few years later, in 1977, the March 4 earthquake devastates the city of Bucharest.

(photo collage credit: Alex Galmeanu)

(photo collage credit: Alex Galmeanu)

Not inclined to let a good crisis go to waste, Ceaușescu decides to rebuild the city on the model of Pyongyang. One quarter of the old city is leveled, and replaced with concrete apartment buildings, to the horror of the lovers of historic Bucharest. The vast majority of the capital's citizens think the dictator has gone mad, yet nobody protests the demolition in the city.

Few understood then, and few understand now why North Korean architecture exercised such a pull on the Romanian dictator. But as any of his other mad decisions, at its core it had a kernel of logic. Here is a clip by Berlin architect Philipp Meuser, who was recently allowed to shoot a few Pyongyang architectural scenes. Despite the totalitarian outlook of the city, it is an architectural jewel, and when one day North Korea will be a free country Pyongyang will be one of the most highly sought tourist attractions especially for its mesmerizing sky-risers and apartment buildings. As Meuser says, modern architecture has always been ideological, and on this Pyongyang offers no exception.

Saturday, January 8, 2011

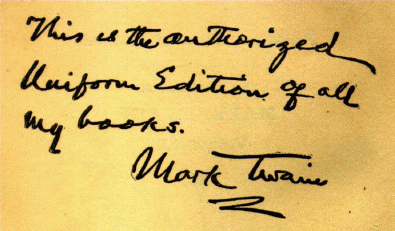

The unobjectionable Mark Twain

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, in a NewSouth Books edition is intended for classroom use, and plans to do away with any reference to the euphemism 'nigger', replacing it with 'slave'. For good balance, the term 'Injun' will be also replaced with 'Indian'. According to the Publishers Weekly, Twain scholar and editor Alan Gribben says: "This is not an effort to render Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn colorblind... Race matters in these books. It's a matter of how you express that in the 21st century."

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, in a NewSouth Books edition is intended for classroom use, and plans to do away with any reference to the euphemism 'nigger', replacing it with 'slave'. For good balance, the term 'Injun' will be also replaced with 'Indian'. According to the Publishers Weekly, Twain scholar and editor Alan Gribben says: "This is not an effort to render Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn colorblind... Race matters in these books. It's a matter of how you express that in the 21st century."Some readers have protested. Diana Senechal, commenting at the Core Knowledge blog, observes that "Changing the “n” word to “slave” distorts the meaning and language. Huck frequently refers to Jim as a “n” but does not regard him as a “slave.” What happens to the sentence at the end of chapter 14?

'I see it warn’t no use wasting words–you can’t learn a slave to argue. So I quit.'

"That’s absurd", writes Senechal. "Huck isn’t commenting on Jim’s slave status; he’s commenting on his race. It’s a racist comment, yes, but it’s blatantly ironic; the reader sees that Huck’s reasoning is no better than Jim’s, and that Jim has done better than Huck in this discussion. And it is in the very next chapter that Huck is humbled–when he plays a trick on Jim and realizes how mean it was."

Ironically, the novel Huckleberry Finn was controversial from the beginning, but not for its typecasting of Jim 'the nigger ... that used to belong to old Miss Watson' and of Injun Joe, the terrible, vengeful Indian - but rather for the reprehensible acts of its young characters. Twain writes:

"When Huck appeared, the public library of Concord flung him out indignantly, partly because he was a liar, and partly because after deep meditation and careful deliberation he decided that if he'd got to betray Jim or go to hell, he would rather go to hell - which was profanity, and those Concord purists couldn't stand it."

Then there's an episode in 1905 when the Brooklyn Public Library officials sought to dispose of the book at the request of a 'young woman, superintendent of children's department, [who] insisted that Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer be removed from the children's room because of their "coarseness, deceitfulness and mischievous practices."'

http://www.twainquotes.com/19351102.html

When asked by the Brooklyn head librarian to defend his two books, the author responded with the following letter:

"Dear Sir:

I am greatly troubled by what you say. I wrote Tom Sawyer & Huck Finn for adults exclusively, & it always distressed me when I find that boys and girls have been allowed access to them. The mind that becomes soiled in youth can never again be washed clean. I know this by my own experience, & to this day I cherish an unappeased bitterness against the unfaithful guardians of my young life, who not only permitted but compelled me to read an unexpurgated Bible through before I was 15 years old. None can do that and ever draw a clean sweet breath again on this side of the grave. Ask that young lady - she will tell you so.

"Most honestly do I wish I could say a softening word or two in defence of Huck's character, since you wish it, but really in my opinion it is no better than God's (in the Ahab & 97 others), & the rest of the sacred brotherhood.

"If there is one Unexpurgated in the Children's Department, won't you please help that young woman remove Tom & Huck from that questionable companionship?

Sincerely yours,

S. L. Clemens" In time, we have become less offended by the mischievous boys in Twain's books - but that is only because their world is now distanced in time and space, and their misdemeanors now look patriarchal and stylized. We would still balk today at a children book with the subject of contemporaneous students stealing and getting away with it, running away from public school taking months long idyllic trolls through the wilderness, drinking water from rivers and eating tree bark. Or maybe we'd accept it as an eccentricity, but Twain seriously believed in the educational benefits of this free roaming life style. For him, the school of life was preferable to the one with classrooms.

In time, we have become less offended by the mischievous boys in Twain's books - but that is only because their world is now distanced in time and space, and their misdemeanors now look patriarchal and stylized. We would still balk today at a children book with the subject of contemporaneous students stealing and getting away with it, running away from public school taking months long idyllic trolls through the wilderness, drinking water from rivers and eating tree bark. Or maybe we'd accept it as an eccentricity, but Twain seriously believed in the educational benefits of this free roaming life style. For him, the school of life was preferable to the one with classrooms.

While some people say that an education is what remains after everything learned has been forgotten, Twain had a simpler version: "Education consists mainly in what we have unlearned". And he had something to say about the entire organization: "In the first place God made idiots. This was for practice. Then He made school boards."

In what regards Mark Twain's views on the depiction of Indians in literature, he wrote an 1870 essay with his usual verve, 'The Noble Red Man', where he's taking a strong view on novels like those of Fenimore Cooper that present the Indian as a Noble Savage.

"In books he is tall and tawny, muscular, straight and of kingly presence; he has a beaked nose and an eagle eye. " [...]

"He is noble. He is true and loyal; not even imminent death can shake his peerless faithfulness. His heart is a well-spring of truth, and of generous impulses, and of knightly magnanimity. With him, gratitude is religion; do him a kindness, and at the end of a lifetime he has not forgotten it. Eat of his bread, or offer him yours, and the bond of hospitality is sealed--a bond which is forever inviolable with him.

"He loves the dark-eyed daughter of the forest, the dusky maiden of faultless form and rich attire, the pride of the tribe, the all-beautiful. He talks to her in a low voice, at twilight of his deeds on the war-path and in the chase, and of the grand achievements of his ancestors; and she listens with downcast eyes, "while a richer hue mantles her dusky cheek."

"Such is the Noble Red Man in print. But out on the plains and in the mountains, not being on dress parade, not being gotten up to see company, he is under no obligation to be other than his natural self, and therefore:

"He is little, and scrawny, and black, and dirty; and, judged by even the most charitable of our canons of human excellence, is thoroughly pitiful and contemptible. There is nothing in his eye or his nose that is attractive, and if there is anything in his hair that--however, that is a feature which will not bear too close examination... He wears no bracelets on his arms or ankles; his hunting suit is gallantly fringed, but not intentionally; when he does not wear his disgusting rabbit-skin robe, his hunting suit consists wholly of the half of a horse blanket brought over in the Pinta or the Mayflower, and frayed out and fringed by inveterate use. He is not rich enough to possess a belt; he never owned a moccasin or wore a shoe in his life; and truly he is nothing but a poor, filthy, naked scurvy vagabond, whom to exterminate were a charity to the Creator's worthier insects and reptiles which he oppresses. Still, when contact with the white man has given to the Noble Son of the Forest certain cloudy impressions of civilization, and aspirations after a nobler life, he presently appears in public with one boot on and one shoe--shirtless, and wearing ripped and patched and buttonless pants which he holds up with his left hand--his execrable rabbit-skin robe flowing from his shoulder--an old hoop-skirt on, outside of it--a necklace of battered sardine-boxes and oyster-cans reposing on his bare breast--a venerable flint-lock musket in his right hand--a weather-beaten stove-pipe hat on, canted "gallusly" to starboard, and the lid off and hanging by a thread or two; and when he thus appears, and waits patiently around a saloon till he gets a chance to strike a "swell" attitude before a looking-glass, he is a good, fair, desirable subject for extermination if ever there was one. [...]"

At that time, literature depiction of natives had no third alternative between the idealized one of Fenimore Cooper and the gaunt one of Mark Twain. The entire Noble Man can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/hns/indians/redman.html - it is a well written diatribe, and one of the most offensively contemptuous pieces ever composed. I'd like to believe that his extermination is one of behavior and of pants kept up with the left hand, and not of actual breathing persons, but I am not too sure.

Twain is as controversial now as he was in his time, and we can enjoy some of his writings while being careful with others, but the last thing we should do is to falsify him especially for young readers. So let Injun Joe be Injun - the word is so rarely used that it's long lost its pejorative bite. I doubt that this word is read in many other places today than in Tom Sawyer. As for the n. word, it can be read like that in class, if 'nigger' is too much, but the text itself should be left as it is. His contemporaries have managed not to edit his more blasphemous passages, and neither should we.

(Parts of this text have been originally posted as a comment on the Core Knowledge blog.)

Friday, September 24, 2010

A few maxims of François, duc de La Rochefoucauld

"In the Age of Louis XIV Voltaire describes the Maximes of La Rochefoucauld" as one of the works which contributed the most towards forming the taste of the French nation and giving its feeling for aptness and precision", writes Leonard Tancock in the 1979 Introduction to the Penguin Classic edition of the Maxims.

"In the Age of Louis XIV Voltaire describes the Maximes of La Rochefoucauld" as one of the works which contributed the most towards forming the taste of the French nation and giving its feeling for aptness and precision", writes Leonard Tancock in the 1979 Introduction to the Penguin Classic edition of the Maxims.Here are some of my favorites. I've done my best to remain true to some of the double meanings in the original...

19 - Nous avons tous assez de force pour supporter les maux d'autrui.

We all have sufficient strength to endure the trouble of others.

22 - La philosophie triomphe aisément des maux passés et des maux à venir. Mais les maux présents triomphent d'elle.

Philosophy easily triumphs over past and future evils. But present evils triumph over philosophy.

64 - La vérité ne fait pas tant de bien dans le monde que ses apparences y font de mal.

Truth doesn't do as much good in the world as its appearance does evil.

89 - Tout le monde se plaint de sa mémoire, et personne ne se plaint de son jugement.

Everybody complains about their memory, and nobody complains about their judgment.

110 - On ne donne rien si libéralement que ses conseils.

Nothing we give away as liberally as our advice.

129 - Il suffit quelquefois d'être grossier pour n'être pas trompé par un habile homme.

To be slow-witted is at times sufficient for saving oneself from a smart trickster.

231 - C'est une grande folie de vouloir être sage tout seul.

It's very foolish to want to be wise all alone.

238 - Il n'est pas si dangereux de faire du mal à la plupart des hommes que de leur faire trop de bien.

It's not as dangerous to harm the majority of the people as it is to do them too much good.

375 - Les esprits médiocres condamnent d'ordinaire tout ce qui passe leur portée.

Average minds duly condemn whatever goes past their reach.

421 - La confiance fournit plus à la conversation que l'esprit.

Confidence gives more to conversation than wit.

447 - La bienséance est la moindre de toutes les lois, et la plus suivie.

Propriety is the least of all laws, and the most followed.

458 - Nos ennemis approchent plus de la vérité dans les jugements qu'ils font de nous que nous n'en approchons nous-mêmes.

Our enemies are closer to the truth in their judgment of our character than we are ourselves.

496 - Les querelles ne dureraient pas longtemps, si le tort n'était que d'un côté.

Quarrels would not last long, were the fault on one side only.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Adam Smith on education

The Wealth of Nations, V.1.181

The Wealth of Nations, V.1.181"...It is otherwise with the common people. They have little time to spare for education. Their parents can scarce afford to maintain them even in infancy. As soon as they are able to work they must apply to some trade by which they can earn their subsistence. That trade, too, is generally so simple and uniform as to give little exercise to the understanding, while, at the same time, their labour is both so constant and so severe, that it leaves them little leisure and less inclination to apply to, or even to think of, anything else.

"But though the common people cannot, in any civilized society, be so well instructed as people of some rank and fortune, the most essential parts of education, however, to read, write, and account, can be acquired at so early a period of life that the greater part even of those who are to be bred to the lowest occupations have time to acquire them before they can be employed in those occupations. For a very small expence the public can facilitate, can encourage, and can even impose upon almost the whole body of the people the necessity of acquiring those most essential parts of education.

"The public can facilitate this acquisition by establishing in every parish or district a little school, where children may be taught for a reward so moderate that even a common labourer may afford it; the master being partly, but not wholly, paid by the public, because, if he was wholly, or even principally, paid by it, he would soon learn to neglect his business. In Scotland the establishment of such parish schools has taught almost the whole common people to read, and a very great proportion of them to write and account. In England the establishment of charity schools has had an effect of the same kind, though not so universally, because the establishment is not so universal. If in those little schools the books, by which the children are taught to read, were a little more instructive than they commonly are, and if, instead of a little smattering of Latin, which the children of the common people are sometimes taught there, and which can scarce ever be of any use to them, they were instructed in the elementary parts of geometry and mechanics, the literary education of this rank of people would perhaps be as complete as it can be. There is scarce a common trade which does not afford some opportunities of applying to it the principles of geometry and mechanics, and which would not therefore gradually exercise and improve the common people in those principles, the necessary introduction to the most sublime as well as to the most useful sciences."

Of the two systems of morality

This was written by Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, V.1.199, published in 1776.

"The former is generally admired and revered by the common people: the latter is commonly more esteemed and adopted by what are called people of fashion. The degree of disapprobation with which we ought to mark the vices of levity, the vices which are apt to arise from great prosperity, and from the excess of gaiety and good humour, seems to constitute the principal distinction between those two opposite schemes or systems. In the liberal or loose system, luxury, wanton and even disorderly mirth, the pursuit of pleasure to some degree of intemperance, the breach of chastity, at least in one of the two sexes, &c. provided they are not accompanied with gross indecency, and do not lead to falsehood or injustice, are generally treated with a good deal of indulgence, and are easily either excused or pardoned altogether. In the austere system, on the contrary, those excesses are regarded with the utmost abhorrence and detestation. The vices of levity are always ruinous to the common people, and a single week's thoughtlessness and dissipation is often sufficient to undo a poor workman for ever, and to drive him through despair upon committing the most enormous crimes. The wiser and better sort of the common people, therefore, have always the utmost abhorrence and detestation of such excesses, which their experience tells them are so immediately fatal to people of their condition. The disorder and extravagance of several years, on the contrary, will not always ruin a man of fashion, and people of that rank are very apt to consider the power of indulging in some degree of excess as one of the advantages of their fortune, and the liberty of doing so without censure or reproach as one of the privileges which belong to their station. In people of their own station, therefore, they regard such excesses with but a small degree of disapprobation, and censure them either very slightly or not at all."